Dan Kelley, principal in MGA Partners, the Philadelphia architectural firm that succeeded the award-winning Mitchell/Giurgola firm when they moved to Australia. Kelley gave a presentation at the South End library on March 12 about the architectural history of the South End branch.

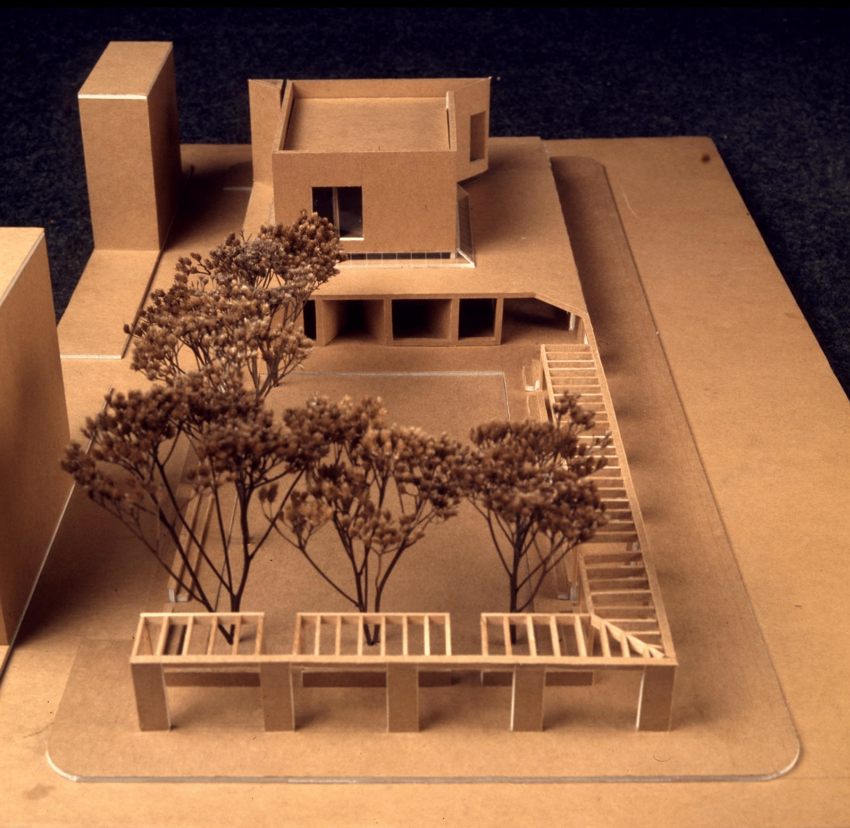

An early proposal by Romaldo Giurgola for a sunken courtyard next to the South End library, with a dug-out lower level

Some of the surprising details that came out during a captivating talk and PowerPoint presentation on March 12 about the architectural history of the South End library: Now located on West Newton Street’s corner, the building could have been sited on the Rutland Square side; the library entrance might have been on Tremont Street; the proposed design included a lower-level Children’s Room (now the basement) that overlooked a sunken courtyard; and there could have been two large reading rooms instead of the one cramped space the library offers today. What might have forced the decision to go for the current, arguably lesser, design? The 1960s budget, for one, suggested architect Dan Kelley in his presentation called Beyond City Hall. It was a grand total of $225,000.

A view from the interior of the library onto a proposed sunken courtyard

Kelley, a principal in MGA Partners, who worked closely with Romaldo Giurgola, the library’s architect, traveled to the South End from Philadelphia at the invitation of FOSEL’s advisor (and assistant professor of architecture at Northeastern) Michelle Laboy. Kelley’s talk focused on the genesis of the library’s architecture and the Philadelphia School, based on research he did in the Giurgola archives at the University of Pennsylvania. The award-winning architectural firm of Mitchell/Giurgola, which in the 1980s built the Parliament Building in Canberra, Australia, was part of a group of architects of he 1960s and 1970s that helped rebuild the city of Philadelphia. .

The 1962 Mitchell/Giurgola proposal for a new Boston City Hall. It came in second.

How Giurgola got the assignment for the South End library is a matter of some speculation, said Kelley. Giurgola, who was awarded the AIA Gold Medal by the American Institute of Architects in 1982, came in second in the competition to design a new Boston City Hall in 1962. Some think that the South End library assignment a few years later was the consolation prize. Progressive Architecture magazine wrote in 1963 that the Giurgola proposal should have won the City Hall competition as it succeeded better than the winner in proposing a design that was “an intimate part of the restructurization of the area, and not an isolated monument.”

Early designs for the branch showed the building on different sides of the lot on Tremont Street

In his talk, Kelley compared Boston and Philadelphia as two cities dating from America’s Revolutionary era that were similar in their once-upon-a-time history of wealth and glory followed by urban decline during the 1950s and 1960s. The Philadelphia School architects were recruited by George Holmes Perkins, dean of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. They were assisted in the realization of their so-called Post-Modern approach to urban architecture by Edmund Bacon, Philadelphia’s city planner, who wanted to rebuild the city in a progressive way. That meant, among other things, to take into account the context, surroundings and social needs of where the buildings were located, as if they were “a fragment” of a larger whole, rather than an isolated structure imposed on an urban environment, explained Kelley.

The final design for the South End library, approved in 1970; it opened in 1971.

The tight budget for the construction of the South End library probably reduced the chances for the more attractive but expensive options of the sunken courtyard and the two large reading rooms on top of a dug-out lower level. Deficient site preparation led to the collapse of a trellis that surrounded the green space in the final design, making it unstable within a short period of time. An abutter to the library attending the presentation reported that refrigerators and other debris were thrown “down there.” In the 1990s the green space was replaced with a park surrounded by an iron fence, which is still there, today.

Romaldo Giurgola (L) walking past the South End library’s construction site

The presentation was well attended by a number of local architects, as well as David Leonard, president of the Boston Public Library. Leonard commented that three ideas struck him: First, the centrality of Library Park to the building’s design; second, the evolution of the library’s architecture and the possibility that the final version of the proposed designs was perhaps not the stronger one and, finally, the question of how the form that suited the function of the library then, is different from what would be the case today, now that libraries have changed so dramatically in how they provide services to library users. Other architects in the audience also expressed interest in Giurgola’s initial designs for the library, especially the ones that included the sunken courtyard, lower level windows overlooking green space, and a library entrance on Tremont Street.

The South End branch of the Boston Public Library is on track for a major renovation and expansion in the next five years, which will begin with a $100,000 Programming Study sometime after July 1, so the history of its current design comes at an appropriate time. In the immediate future, the library will receive a so-called “refresh,” with new carpeting, fresh paint, additional electrical outlets, a reconfiguration of the furniture and new seating arrangements paid for by FOSEL’s private fundraising last year.